Business acquisitions and sales are not solely the domain of international corporations. Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in Switzerland are increasingly confronted with issues relating to corporate transactions and succession planning. Sometimes the focus is on a traditional succession, sometimes on strategic growth, or on the involvement of investors. For many entrepreneurs, however, this is not an everyday step – rather, it is one that comes with significant legal, tax, and emotional challenges.

We provide you with an overview of the common transaction topics in the SME environment. We show you the options for SMEs to transfer or sell a company – whether within the family, to the management, or to external buyers. In addition to legal aspects, we also highlight significant tax pitfalls.

1. Internal and External Succession Solutions – The Main Options

Entrepreneurs who wish to actively shape the future of their business have several options. Each option opens up its own opportunities – whether by ensuring continuity, creating fresh momentum, or providing additional resources. The decisive factor is which solution, and long-term vision best matches the entrepreneur’s goals and the company’s needs. Each path offers different perspectives for growth and further development.

Family Succession – Preserving Values and Continuity

Transferring a business within the family allows the entrepreneur’s life’s work to continue and preserves the corporate culture. It also provides an opportunity to safeguard values and traditions across generations. With careful legal and financial planning – for example, through clear inheritance arrangements concerning compulsory portions or through staggered transfer models – this path can become a sustainable solution for all parties involved.

Management-Buy-Out (MBO) – Succession in Trusted Hands

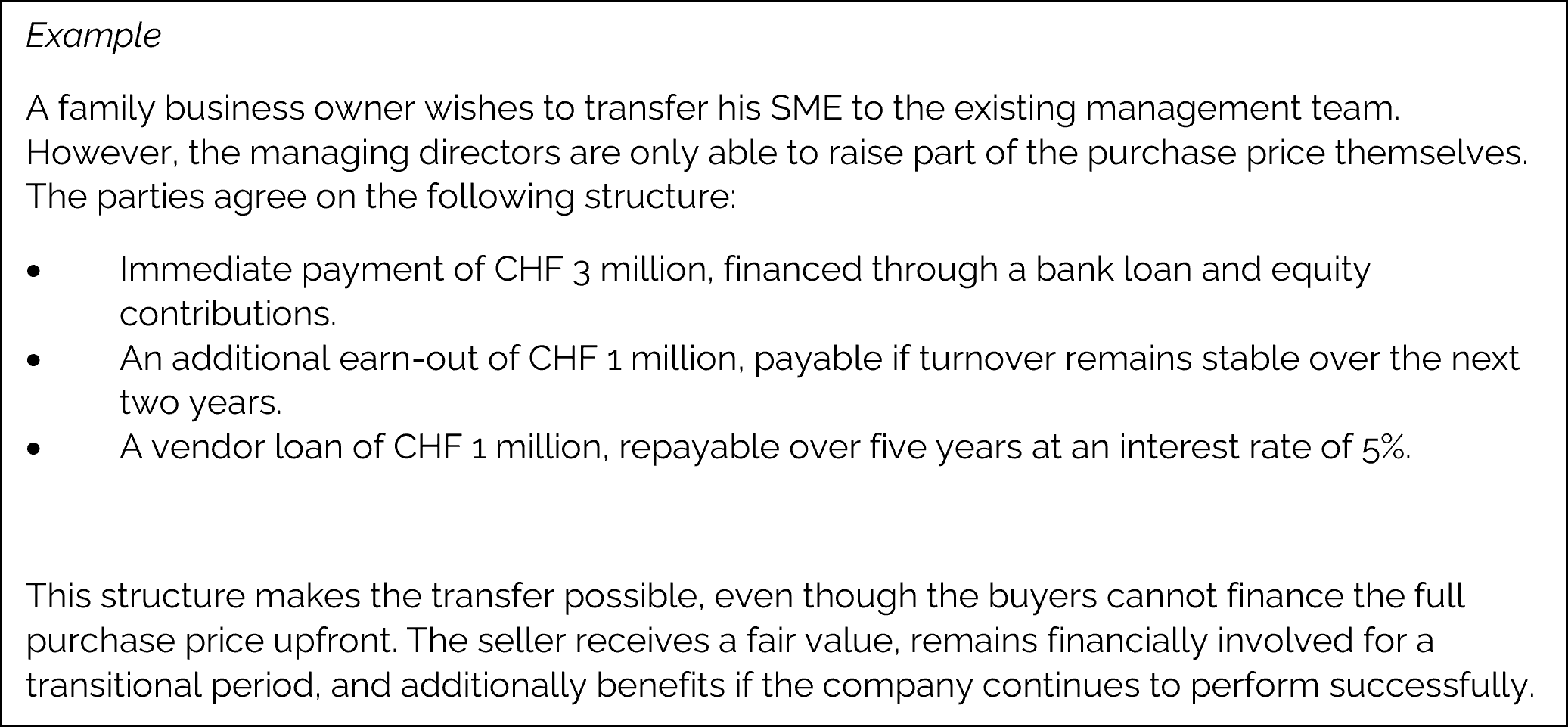

In an MBO, the existing management team takes over the company. The major advantage: the business remains in familiar hands, and the executives can seamlessly continue the established strategy. The know-how of experienced leaders is preserved. Employees, customers, and management already know each other. Because there are fewer information asymmetries, the transaction is also legally easier to structure.

With suitable financing instruments such as vendor loans or earn-outs, even larger deals can be implemented. This creates a solution that combines stability with entrepreneurial commitment. However, potential role conflicts must not be underestimated when former employees suddenly act as buyers.

Management-Buy-In (MBI) – Fresh Perspectives from Outside

An MBI brings fresh perspectives into the company. External executives take on responsibility and contribute new ideas as well as additional expertise. For SMEs, this can be an ideal path to reposition the business or enable further growth. With careful preparation and clear legal frameworks, cultural differences can be mitigated, and opportunities optimally leveraged.

Unlike an MBO, an MBI may lead to greater friction with employees, suppliers, or customers. In addition, due diligence reviews are generally more extensive.

Sale to Third Parties

A sale to a strategic or financial investor often offers the greatest development opportunities. Strategic buyers can realize synergies, while financial investors provide capital and networks. For the seller, this not only means an attractive purchase price but also the opportunity to see the company grow in a larger context. With the right contractual safeguards – such as non-compete clauses or transitional arrangements – it is possible to ensure that the corporate values are preserved in the future.

2. Business Acquisitions as a Growth Strategy

Not every transaction is driven by succession. Many SMEs use acquisitions primarily as a strategic tool:

- Access to new markets: Instead of growing slowly and organically, companies can gain immediate access to new regions or industries through acquisitions.

- Synergies and economies of scale: Shared administration, procurement, or production reduce costs.

- Technology and innovation: Especially in the technology sector, companies acquire startups in order to secure know-how, software, or patents.

- Competitive position: Acquiring competitors can strengthen or expand a company’s market position.

From a legal perspective, a strategic acquisition means that contracts are often tailored to integration issues. Typical clauses include securing the transition of key employees, protecting goodwill, non-compete obligations against the seller, or warranties regarding the functionality of IT systems.

3. Asset Deal vs. Share Deal

The transaction is typically structured either as a share deal or as an asset deal.

In a share deal, the buyer acquires the shares of the company – i.e., the shares of a company limited by shares (AG) or the capital contributions of a limited liability company (GmbH). The company remains as a legal entity. The buyer thereby acquires control and “indirectly” the beneficial ownership of the business.

Advantage: Employment contracts, licenses, and supply agreements continue unchanged. In addition, under certain circumstances, capital gains are tax-free.

Disadvantage: The buyer also assumes all “legacy issues,” including (hidden) risks such as pending litigation or tax claims. This is why share purchase agreements contain detailed warranty catalogues and exclusion clauses.

In an asset deal, the buyer acquires specific assets (real estate, machinery, customer contracts) of the company. Employment relationships generally transfer automatically to the buyer, while other contracts usually must be individually transferred or renegotiated. Especially where assets are directly owned by the entrepreneur – for example, in a sole proprietorship – the transaction typically takes the form of an asset deal.

Advantage: The buyer can “cherry-pick.”

Disadvantage: High administrative effort and often tax disadvantages, since hidden reserves are revealed.

4. Typical Conflict Areas in SME Transactions

Business transfers and succession planning rarely proceed without conflict. Common problem areas include:

- Family and inheritance law: Compulsory share claims, unequal treatment of children, and unclear roles often lead to disputes. Inheritance agreements, shareholders’ agreements, or family constitutions may help.

- Management and employees: In MBOs or MBIs, interests collide, loyalty as an employee versus toughness as a buyer. When a company is acquired by external parties, employees may experience insecurity, increasing the risk of departures.

- Valuation and price finding: Business owners often have an emotional attachment to “their” company and expect a higher price, while buyers calculate objectively. Earn-outs and vendor loans are common tools to bridge differences.

- Taxes: Incorrect transaction design can trigger significant tax consequences (for example, in the case of a so-called indirect partial liquidation).

- Governance: Especially in partial sales or when investors come on board, conflicts often arise about decision-making powers. Shareholders’ agreements can provide clarity.

5. Tax Pitfalls at a Glance

It is often assumed that the sale of company shares is always tax-free for the seller. This assumption, however, is misleading, as in practice various scenarios may lead to a significant tax burden.

Particularly relevant is the so-called indirect partial liquidation: If a private individual sells at least 20 percent of the shares in their own company to a buyer who holds the participation as business assets, and the buyer distributes non-business-related assets (already existing at the time of sale) within five years, while financing the purchase price from these non-business-related assets, this triggers income taxation for the seller.

Another problematic scenario is transposition, where an individual transfers shares from their private assets to a holding company under their control. If the purchase price is overstated – i.e., higher than the nominal value – or if it is financed from the company’s own funds, the proceeds may be reclassified as taxable income.

Finally, real estate gains tax must not be overlooked. If real estate is part of the business assets, a sale can be treated for tax purposes as a disposal of property – with corresponding taxes levied on the realized gain.

Despite clear practical guidance from courts and tax authorities, the tax treatment always depends on the individual case and requires careful planning and structuring. Those who address these issues at an early stage can avoid unexpected burdens and structure the transaction in a tax-efficient manner.

6. Purchase Price Structuring

The question of purchase price is almost always the decisive issue in company sales. Entrepreneurs want a fair price for their life’s work, while buyers aim to mitigate risks. In practice, flexible models help reconcile these interests – in particular through earn-out clauses and vendor loans.

Earn-Out-Clauses

An earn-out means that part of the purchase price is paid immediately, while another portion depends on the future performance of the company. This way, the buyer carries less risk, and the seller benefits if the company continues to perform well. A clear definition of the targets is crucial to avoid later disputes.

Vendor Loans

In a vendor loan, the seller finances part of the purchase price in the form of a loan to the buyer. This seller’s loan is repaid over several years, usually subordinated to bank loans and bearing a market rate of interest. For the buyer, this is often the only way to secure the necessary financing. However, the seller does not receive the full purchase price immediately but assumes a certain degree of risk by deferring payment.

Thus, earn-outs and vendor loans often make SME transactions possible in the first place.

7. Key Legal Aspects – Warranties, Liability, Contracts

In every business transfer, legal details also play a decisive role. Of particular importance is the issue of warranties. Under the Swiss Code of Obligations, the buyer must notify the seller of defects without undue delay; otherwise, the buyer forfeits his rights. In addition, statutory limitation periods apply. While the parties may contractually exclude or limit warranty claims, such an exclusion does not apply if the seller has fraudulently concealed defects. For this reason, share purchase agreements regularly contain very detailed representations and warranties that deviate from the statutory provisions. The seller may, for example, warrant that the financial statements have been properly prepared, that no hidden tax liabilities exist, that all social security contributions have been duly paid, or that no litigation is pending which could materially affect the company’s value. For the buyer, these warranties are essential, particularly in a share deal, since he assumes all risks associated with the company.

In addition to warranties, indemnity clauses are also common. Under such provisions, the seller undertakes to hold the buyer harmless from specific risks or liabilities expressly identified in the agreement. These arrangements create legal certainty and help prevent a transaction from being undermined afterwards by unforeseen burdens.

Another key area is the shareholders’ agreement. As soon as several persons are involved – whether through a family-internal transfer or the entry of investors – there is a need for clear rules among the shareholders. A shareholders’ agreement defines how decision-making rights are allocated, which resolutions of the general meeting and the board of directors are particularly important and therefore require special majorities, whether pre-emption rights for co-shareholders apply, or whether minority shareholders may also sell their shares in the event of a sale by the majority (so-called tag-along right). Conversely, it is also common to stipulate that minority shareholders must sell their shares if the majority of shareholders finds a buyer (so-called drag-along right). Such provisions prevent deadlock situations and safeguard the company’s ability to act.

Finally, in the context of family businesses, the concept of family governance also plays an important role. This is not merely about legal agreements, but about shaping a common “constitution” for the business family. Such a family constitution sets out values, principles, and decision-making mechanisms intended to provide guidance across generations. Although a family constitution does not carry the binding legal force of a shareholders’ agreement or articles of association, it nevertheless creates clarity and serves as a moral compass to prevent conflicts between generations or among heirs.

This makes it clear: legal protections are not mere formalities, but the key to ensuring that a transaction endures over the long term. Without precise warranty and liability provisions, without a clear shareholders’ agreement, and without a forward-looking governance structure, risks arise that can quickly jeopardize the success of a deal.

Conclusion

SME transactions are a complex interplay of economic, legal, and tax factors. Whether a family-internal succession, an MBO, an MBI, or a sale to an investor – each option carries opportunities, risks, and potential for conflict. Those who plan early, establish clear structures, and address the legal as well as tax aspects in a professional manner, significantly increase their chances of success. In this way, the course can be set strategically for a successful future.

If you are considering selling your company, acquiring a business, or planning a succession solution, it pays to address the legal and tax questions at an early stage. We provide comprehensive support – legal, tax, and strategic – to ensure that your transaction becomes a success.